There were many Saturday nights I didn’t get asked to babysit. I can’t say why. Perhaps the Miller’s used someone else on occasion, but whatever, Ray and Mae Miller were always with the Saturday night gang. On Saturday evenings I rode with my parents to Richard’s house. They waited for the other half dozen or so couples to arrive. They all left together, car-pooling to wherever they went. They left we kids on our own.

Richard (pictured left) talked about cars constantly, he was obsessed with the automobile. He couldn’t wait to drive, but he had no choice. We were both fifteen, too young to get our licenses. I was several months the older. I would be sixteen that June. I think his sixteenth birthday was early 1958, the next year.

Now, all the couples that joined mom and dad and the Wilsons on Saturday nights doubled up and car pooled, squeezing into just a couple vehicles. They shared different cars each time they went out. They left the other cars in the Wilson’s large parking area. Most of the time they left the keys in their cars. It wasn’t long before we were picking out a car to borrow.

We didn’t call it “stealing”. After all, we were only going to take the car for a couple hours or so and bring it back safe and sound. Sure, we’d burn a bit of gas, but who’d really notice?

Borrowing cars quickly became our regular Saturday night

pastime. We would take whichever car had keys and joyride through the countryside. Those doing the borrowing varied from week to week. Sometimes there was just Rich and I. (There was always Rich and me.) Occasionally Tommy Wilson, and even Suzy, was along, but only if we couldn’t avoid taking them. We had to be careful. We were always under the threat that they would blab. There were times Jim Whitlach (pictured right) was a passenger. He was a friend of Richard’s who lived down on Route 23. Richard was in the same classes at Warwick School with Jim and they had become friends before I moved to Bucktown. I didn’t care much for Jim. He was kind of a hood and

tough talker. Tom Frame (left) also joined us on some of these outings. Tom was quiet and likable. He was also the best mechanic in our group. None of us were driving age, though, so there wasn’t a single driver’s license among us.

Sometimes we would stop at Rock’s, a drive-up restaurant just outside Pottstown, not far from my house. Actually it was closer to my place than to Pottstown. It had been built recently and Rock’s assumed the roll of the local hangout for teenagers in the county South of Pottstown. The

restaurant closed years ago, but the building remains and looks about the same. There is a slanted glass window to the front, with two small sliding doors near the bottom. You ordered and received your food at these little openings and could eat in your car or you could go inside, which was a regular sit down restaurant. It had an Italian themed mural that ran round three of the walls. Weusually ate in our car. I would go inside with my parents, and later on dates.

We usually began our excursions into Pottstown to drag the main strip through the center of town or some nights we drove wildly over the back roads with the lights off, thinking this way no one would see us speeding along, such as the county police. It was important to not have a confrontation with the local cops, not when driving without a license in somebody else’s car. The East Vincent Township police were like a cliché out of a movie about back country cops. Stories circulated about how so-and-so was pulled over for a broken tail light. Oddly, the tail light didn’t get broken until he was stopped on the side of the road and the officer walked by it with his night stick. We always made sure we got home well before 2:00 AM. There were times we almost didn’t make it. We actually seldom saw a township cop, except those sometimes have coffee at Rocks.

You know a broken tail light is known as a mechanical failure and a moving violation, especially on a “borrowed” car driven by an unlicensed teenager. We never experienced any broken tail lights, but we had our share of mechanical failures. But we were never confront by any police.

One of the regular couples going out with my folks were named Moses. They had a gray car, but I don’t know the make. It was a coupe. We’d never taken it before, but night it was the first in line and the keys were hanging in the ignition.

If case you are wondering about all this carelessly leaving cars unlocked, it wasn’t a big deal in those days. My dad never locked anything. We’d go to the movies in Coatesville and he’d leave the car unlocked. He did take the keys with him, though. He never locked the house doors either. Times were different then, plus we were country and small town people. Everybody kind of trusted each other. Besides These cars were parked on a friend’s driveway out around almost nothing. Leave the car unlocked with the key inside, no big deal, whose going to take it? Now granted, leaving the key hanging in the ignition was a bit over board. People usually stuck them under the floor mat or in the ashtray (that’s another thing, almost all cars had ashtrays then). The Moses’ probably got out in a hurry when they arrived and simply forgot, thank you very much.

We took the Moses car and had a grand time on the back roads. It

had a little oomph to it, a kick going through the gears. The ride was somewhat rough, kind of bouncy. We didn’t care. We had the radio pumped up load listening to “the pound of sound” emanating from WIBBAGE in Philadelphia, the great WIBG Radio 99, and we were having a rolling party. WIBG had previously been a religious station. It’s call letters WIBG had stood for Why I Believe in God.

Around 1:00 AM we knew it was time to hustle home, we were all ready cutting it close. Thing was we were on a narrow country road going in the wrong direction. We needed to get turned about and go the other way. Richard was driving and he saw a cornfield with a wagon trail running up between a fence row and the corn. He figured this would be an easier turn around than attempting a three-pointer on the narrow road. He pulled into this skinny lane, basically two wheel tracks running between obstacles on each side. He went in about two car lengths and stopped and flipped the shift into reverse. When he went to back up he couldn’t. The car had no reverse. It sat there doing nothing. I think there was a humming sound. We looked at each other. Finally some of us got out, Richard put it in neutral and we pushed. Once on the road pointed the right way we jumped back in and took off. We knew there was nowhere to go but straight ahead.

We weren’t averse to snatching bigger game. One night, Rich and I were the only ones left at the house. We looked at the cars in the drive and then decided to take his dad’s dump truck. His dad must have allowed him to drive it in their lane. He didn’t appear intimidated by the extra gears and all the other rigmarole about the cab. He drove it out and down Route 100 without too much gear grinding.

Richard didn’t turn off into the side roads, but drove us right into Pottstown. We were bouncing along on some of the north section streets when he slammed over a curb tuning one corner. Something heavy fell off the truck into the street with a great bang. It sounded awfully huge and maybe whatever went astray was too much for two boys to lift. We didn’t stop to find out how strong we might be. Rich tromped the accelerator and we got out of there. I don’t know what fell off or if his dad ever noticed. Richard never brought it up, so I left it alone. We did decide to leave the truck alone too after that.

The closest we came to disaster and its sweet companion of death was a night we drove my dad’s car out. Yes sir, the joyride was going along smooth and fast. Tommy Wilson, Jim Whitlach and Tom Frame were with us. It was my family’s car so I drove.

It was getting late as we were cruising up a hill near where Ray Miller lived. Once I passed his house we topped the hill and started down a long decline. Not sure of the exact location anymore, might have been on Fulmer Road near Pigeon Creek, but anyway this part of the road continued to slope downward for several miles and it went through a series of S-curves. A the end of the curves was the town of Royerford, so we were going away from our homes.To the right of the road at every single S-curve the ground fell away over a steep embankment.

I was doing about fifty when I crested the top and picked up more speed on the down slope, too speedy to feel comfortable. I tapped the brake and the pedal went to the floorboards with no impediment. It went further, faster than if a had slammed down some giant foot upon it. There had been no resistance what-so-ever. I grabbed the emergency brake arm and yanked for all I was worth. It felt like I would pull the lever out of the floor by its roots. I expectedly hand to hit the roof. But nothing happened to slow the car.

“We don’t have any brakes,” I yelled.

Everybody laughed. They didn’t believe me.

We came upon the first of the S-curves. There was no shoulder. The road simply drooped off an embankment on the right side. I swung the wheel as hard as I could and we squealed around, ever picking up speed and barreling toward the next S-curve. The guys weren’t laughing now. The force of the turn had knocked reality into their heads and fear into their hearts. I was too busy steering to be

scared.

There were four S-curves we passed and four loud squeals, but I got us through them. It was a good thing those old Studebakers had a low center of gravity (pictured left a 1953 Studebaker like my dad’s, same color and all). The car eventually drifted to a stop on the long flat stretch at the bottom of the hill. I lay my head against the wheel panting. Darn, we still had to drive the thing home!

I was shaking.

Richard and I traded seats and he drove it back to his house, low gear all the way (pictured left Richard’s home from the air).

We parked it where we found it. Around two-thirty the party animals got home. They said their goodbyes and the driveway grew quiet. My parents called me to go home. I got in the backseat without a word. What could I say? After all, how could I know the car’s brakes were gone?

The Wilsons lived on a hill. It flattened out as a plateau where their house and parking area was. The drive went flat about fifteen feet and then dipped sharply down the hill. It leveled for a short distance at the bottom and dead-ended into Route 100. There was a blind curve up the pike on the left. Dad would have to make a ninety-degree turn to the right to head in the direction of our house. If you went straight across the pike you would go over another embankment straight down through brush for several yards.

I braced myself, scrunching down in the back seat. Dad went over

the hump of the drive and discovered he had no brakes. My mother began screaming. The car picked up a lot of speed on that sharp decline, but dad made the turn and got us home. I’m glad he was a professional driver with a lot of experience.

I kept my mouth shut. I didn’t tell my parents about this until the night of their fiftieth wedding anniversary. I told everyone that night. I wrote it into the speech I gave and treated it with a lot of humor. There wasn’t much humor the night it happened.

Not every “borrowing” ended in drama. Most nights we just had fun. The stupidity of what we were doing never crossed our minds. We continued driving at reckless speed through the dark nights over the back roads without lights on so no police spotted us. We considered ourselves cool when what we were was dumb.

Still, there was this one time with just Rich and me cruising about in his parent’s Dodge when we picked up a girl to in in our madness. Her name was Dot and she lived in an apartment building on the outskirts of Pottstown. It was rather late in the evening. We pulled up alongside the building and Rich tossed a stone against her bedroom window. She looked out and he motioned her down. She came down the fire escape and got in between us. She had just gone to bed and was only wearing her see-through Baby Doll Nightie. (pictured left are Baby Doll’s of that era). In the right light I could see through the top. We drove directly up the main drag of Pottstown—yes, the main drag, and right out Route 422 and took her to Phillips’ Tropical Treat for milkshakes.

You parked under a roof along he parking lot, with speaker post

much like in the drive-in theater. Ere you pressed a button, spoke your order, and in a short time out would come a carhop on roller skates with tour food on a tray that fastened to your side window.

Some nights were worth the risk

.

We took a risk driving that girl through the middle of Pottstown to Phillips’ Tropical Treat. The township was very Blue Nose at that time. They ticketed if you crossed the street against the light or anywhere except at the corner. They had a nine o’clock pm curfew on teenagers. The first showing at the movie theater left out at 9:00 pm, so they allowed a little leeway for going from the theater, but if a cop had seen us we might have been pulled over. It was well past 9:00, almost 11. Wouldn’t that have been a nice pickle, two fifteen year olds illegally driving someone else’s car with a half-naked girl passenger.

The risks of taking other people’s cars on joyrides did not deter us. We continued the practice through the spring into that summer.

When I was living in Downingtown I tried desperately to get a

nickname, attempting to get people to call me “Spider”. I kept trying, but everyone kept ignoring me. The closest I got was Mantis or Daddy Longlegs, which I didn’t like. Kids used those as derogatory reference to my gangly arms and legs. No cognomen ever stuck, which in Downingtown was probably a good thing since most sobriquets I heard were derisive. Nobody wants to get stuck with the epithet Quasimodo. Some may consider the one I finally earned just as bad. “Frank” became my nickname, short for Frankenstein.

“They’re both monsters, aren’t they?”

No, actually neither is a monster. Quasimodo was a deformed human being. The hunchback really represents the near standard of a human who is flawed, but with kindly and protective tendencies, especially in comparison to the handsome, but shallow Captain Phoebus, who is more the real monster.

Frankenstein was the scientist who created the monster not the monster itself. I was the slightly hunched-backed boy who created horror stories. I don’t know how much my classmates knew about my writing in Tenth Grade. We did write some short stories in English and I got teacher recognition for mine. Besides “Rescue” there was another, “Purgatory Story”. But these weren’t Horror stories per se.

“Rescue” concerned a young man stranded on the side of a cliff. “Purgatory Story” was about a group of teenagers who became lost in a cave. Both stories had twist endings, which weren’t happy ones, but they weren’t horror. They were more adventure-suspense tales, or perhaps thrillers.

Then he saw a person across the way. He squinted and was surprised to see Bob. Bill shouted. He watched as Bob heard and looked around. Bob saw him. He waved and Bill waved back.

“Help me, Bob. I’m trapped.”

“You putting me on?”

“No, honest. Elk fell into the quarry. I think he drowned. You gotta help me.”

“You sure you can’t get out?”

“Yes. The cave is a labyrinth inside. Nobody could find the way through, especially without a light. Mine burned out. Besides part of the way fell-in. I’m really trapped, Bob. Help me.”

“No.”

“What?”

“No. You got what you deserved. Look what you did to me, big-shot Bill Liance. Has to be the big man all the time. See where it got you.”

Bob left and Bill stared after him. He had known him all his life and although Bob was easy to tease, he had liked him and though he was liked in return. No, Bob wouldn’t walk off and let him perish.

Bob reappeared on the far ledge. He had something draped over his one shoulder. “Bill,” he called.

Bill waved.

“Look.” Bob said, and he pulled a looped length of rope off his shoulder and held it out in the air. “See this?”

“Yeah?”

“Catch.” Bob threw the coil out into the space between them. It curved downward and fell to the water.

“Bye-bye, Billy,” Bob said and he left.

He was sure Bob would soon return with help, but when night came and then another sun came up, he knew Bob had not lied. He wasn’t going to help.

Excerpt from “Purgatory Store”

In my collection Acts of the Fathers, 1962

Still I was sort of a 1950s style “Goth”. I was known for what I read and talked about. When called upon to do a book review I always selected what I thought were Horror books. I mean, who knew “Buried Alive” by Arnold Bennett (pictured left) would not read like something by Poe? It was difficult enough plowing through Bennett’s 1908 writing style to then discover nothing that horrific ever happens. This was the opening of the novel, “Chapter one: The Puce-Dressing Gown:”

The peculiar angle of the earth's axis to the plane of the ecliptic-- that angle which is chiefly responsible for our geography and therefore for our history--had caused the phenomenon known in London as summer. The whizzing globe happened to have turned its most civilized face away from the sun, thus producing night in Selwood Terrace, South Kensington.

If that doesn’t pull you right into the novel, what does? And puce, really? What guy talks about puce? When I was 15 I didn’t know what puce was. Closest thing I thought of was puke, which pretty much summed up my opinion of “Buried Alive”.

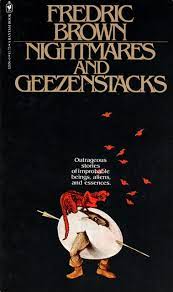

What I read was generally in the horror or science fiction genres, books or collections of stories by Richard Matheson, Ramsey Campbell, Frederic Brown and Ray Bradbury.

One weekend while visiting with Stuart Meisel he said, “I want to show you something.”

He went upstairs and came back with a paperback book. He handed it to me. The book was a bit worn with a creased cover and tattered edges. The title was The Lurking Fear and Other Stories.

“This is the scariest stuff I ever read,” he said.

The book was by someone I had never heard of before, H. P. Lovecraft. He insisted I borrowed the book to read.

During the next week I lay down on our living room floor one bright day. No one was home. The sun was shining through the front windows and I lay in these blocks of light it made around me and read. I became so engrossed in the stories that when a passing shadow of s truck broke the light I screamed. I couldn’t ever read the book at night.

I added Lovecraft to what I carried about school in my hip pocket.

To tell the truth, up until I started writing my autobiography I believed I didn’t get my nickname, “Frank”, until Twelfth Grade after I did a showcase reading of my short stories at school. I was looking for a picture in my 1957 copy of The Torch, the school yearbook for 10th grade, when I read the inscriptions on the back page. These were autographs I got from some of my classmates at the end of Tenth Grade. All but one was addressed to Frank, Frankie or Frank-in-stine (sic). One inscription also reminded me of something else.

“Frank-in-stine, to a real witty classmate. Always remember our trip to Audubon. Jeanette.”

Jeanette Richards (pictured left) was one of the most desirable girls in my class. I doubt she would have ever gone on a date with me since she had her pick of every guy in school, but she did become a friend and part of what I might call my gang. In fact, most of those who signed that page would be in that clique. Homer, Wyatt, Jon and Phil were among the signers.

Mr. Brown of Biology had sponsored the trip to Audubon and the Meadowbrook Bird Sanctuary. Nothing

bonds a group like traveling twenty miles in a cramped van and spending a day traipsing through woodland together seeking out Hairy Woodpeckers and White-Breasted Nuthatches. The group began accepting me as an equal part of the class on that expedition.

Beating the bushes for Black-Capped Chickadees didn’t get me my nickname. Toting around those genre books and talking about writing my own horror stories accomplished that.

When school ended in June of ’57, I got a job picking strawberries at Ridge Farm. The field was located along Route 23 about a mile walk from my home. I had ambled down the Bucktown Hill early one morning , past the slaughterhouse, and inquired at the barn if they were hiring help. I started the same day.

There were no Daddy Longlegs in the strawberry bushes. There weren’t any insects so I guess the farmer sprayed his fields. It was grueling work. There was no shade whatsoever. You went up and down the field towing a little cart of baskets. You duck-walked the rows all day plucking the ripe berries. When you filled all the baskets on your cart you pulled it to the back room of the barn.

The farmer’s wife oversaw this operation. She would tally your

baskets each time you came in. You got fifteen cents per full basket. (I forget the size of the baskets, they weren’t real big, perhaps a quart.) After counting your yield, she inspected the front and back of your hands for any stains. If you got juice on your skin it meant you damaged some of the product. If she found any such incriminating evidence, she deducted five cents a basket for that load. If it happened enough times, she fired you. I got into the habit of not clipping my fingernails short on this job. The best way to pick was to grasp the stem above the berry and clip it off between your thumb and index nails. This procedure slowed your production, but was the only way to avoid staining your hands.

What can I say, it’s a living. I hear people saying Americans won’t do this kind of labor anymore. I’m not sure I believe that. Why not, it’s honest work?

I always paused passing the

slaughterhouse at Routes 100 and

23. The owner collected exotic cattle. He had long-horn steers and American Bison, and these strange short-legged cows covered with long hair.

But he also butchered cattle in the barn. I watched this procedure one day. The brought a steer in and banged in over the head with a sledge hammer. It was then hung up by the rear feet by ropes hanging from metal hooks. Someone finally slit open the belly with a large knife. This made a terrible sound as it cut; rip-p-p-p-p! The blood ran into a trough beneath, and before you could blink they had carved up that beef. It brought back memories with my grandfather killed the chickens when I was a boy. He tied the animal upside down by the feet and slit the throat with a piece of wire.

My mother gave me a surprise sixteenth birthday party in late June. Like the last one in Fifth Grade, she invited some kids I wouldn’t have and missed inviting some who I would. I don’t remember a great deal about this party. I recall we played a morbid game in the dark. Mother passed about various items and told us these were parts of a dissected man. We had to guess what the part was. The person who got the most right won a prize. There was macaroni for veins or some such thing. Grapes represented eyes.

The only gift I still remember was from Ronald Tipton. He gave

me a record album of Gospel songs by Mahalia Jackson. He said, “I know you like her.” I don’t know where he got that idea. I liked Gospel songs, but not her style of singing them. I am not sure I ever heard her sing before that night.

Ronald came with a date, (( Patty Daller left at a

Downingtown class reunion). She left the party with another boy, Charlie Crouse, leaving Ronald without a ride home. His father had to come pick him up. I don’t know why this other boy was even invited. He wasn’t from Downingtown and I didn’t even know him. Maybe he crashed the party. Patty told Ronald she doesn’t remember the instance.

There were a number of other parties over the next year I enjoyed more than my own birthday bash. Richard Wilson and Joan Boder

threw most of these. They were just get-togethers at each other’s homes. It was dancing and food. ( Left, me dancing with Joan Boder. I did take her out a few times.)The attendees were friends of Richard’s mostly, almost everybody younger than I because Richard was two grades behind me. Girls wanted to dance with me at these parties because they considered me a good dancer. We all knew each other as friends. I wasn’t steady dating anyone attending, although I spent a lot of the time with Joan.

Although we seldom played games, there was one we did. It was at a party at Richard’s. There was a cookout in the late afternoon, and as the sky grew dark everyone drifted onto and around the rear porch. The adults kind of hung on the edge in groups, drinking beer, smoking and talking. As the evening wore on their talking grew louder and was interspersed with loud guffaws. We teenagers meanwhile began dancing in the center to music Richard played on his record player. Eventually the night turned a little chill and the adults moved inside the house.

We kids, probably warmed by our jumping about to the rock beats, took over the porch dancing what was called the Bop. Eventually less and less of us were dancing. Instead we were sitting down where we could or stood leaning on the railing. Suddenly the music stopped and Richard picked up the record player and stepped down on to the ground.

“Hey, you wanna play a cool game,” he said.

He was waving a large flashlight about and he used it to lead us out to the garage. The cars were outside and when our little parade marched inside we saw he had set a group of chairs in a circle. H set the record player down on a workbench next to a wall outlet and plugged it in. It was very dark in the garage. The only illumination came from the flashlight Richard held. He proceeded to explain the game. As he did he shown the light in our faces and then the circle of chairs, and then he handed the torch to his brother. Tommy didn’t participate in the game; he manned the record player. It was musical chairs with a twist. The boys sat down on the chairs and the girls circled around them while the music played. During this time the flashlight was snapped off and it was almost pitch black inside the building. When Tommy suddenly stopped the music the girls had to jump on a boy’s lap.

I did not enjoy the game. As soon as the first girl jumped on my lap I got an erection that would not go away. I could not

make out any faces in that dark, but I sure could feel each girl’s bottom pressing across my thighs. Some of them would sit still until the music restarted. Some of them twitched or bounced around impatiently. I could feel the heat of them as well as the weight.

I spent the whole game trying to avoid having the girl feel my

condition when she jumped on my lap. Most of the time I failed in my attempts, especially if she was one of the bouncers. Some girls kind of leaped on to me and some sort of climbed up, grabbing me where ever they could to aid their mount. I wanted to help them, but was fearful of touching them. I didn’t know exactly what my hands might grab in the dark. Frankly, I didn’t know what to do with my hands. I was inclined to fold them over my lap, but what if a girl felt my hands beneath her bottom when she jumped aboard? What would she think I was up to? I gritted my teeth and kept my hands pinned close to my chest. Fighting to keep hands off, though in my opinion most of the girls were landing right in the worst possible spot. I felt embarrassed for the girl as well as myself believing each and every one was discovering my condition. All I heard around me were giggles, laughs and occasional shouts. Everyone else appeared to be having a good time. I was too naïve to understand what I wished to avoid was the real object of the game.

I had turned sixteen. The day after my birthday I was at Motor Vehicles applying for my Learner’s Permit. Even though I would be taking driver’s Education at school next semester, it was required in Eleventh Grade, I wasn’t going to wait around another six months to get my license. I had gotten a lot of practice in during the spring on the back roads in all kinds of vehicles. I was an experienced driver, although no one knew how I became so. I took my driver’s test in the first week of July.

And I failed.

I had no difficulty with the written exam, which was the part I was most concerned with. You are given about a dozen random questions that are taken from anywhere in the Driver’s Manual. It seemed like a lot of material to have to memorize, but the questions were fairly basic.

I aced that part.

I was sent outside behind the building and then ushered to a test car. I got in the car for the road test next to this big State Trooper. He was very intimidating. He spoke in that clipped military style. “You will start your car and drive to that stop sign. Once there, you will turn right.”

I remembered to check my seat position and adjust my mirrors. Cars did not have seat belts yet. I drove toward the stop sign and I put my arm out the window to indicate I was stopping. I stopped. I pointed over the roof that I was going to turn right. Some cars had a new devise called turn signals, but even if you did have such a devise, you were required to use hand signals in the test.

I breezed through the parallel parking and the weaving through cones.

“Go halfway up this hill, stop and turn off the engine,” he ordered.

Ah, yes, what some people thought was the hardest part of the test. People were afraid they would stall the car trying to start up again from a dead stop on a hill. It was a matter of not popping the clutch between releasing the brake and giving the car enough gas to overcome gravity and inertia. Yes, we learned on a stick shift. Automatic transmissions were also a rarity in those years. There was very little on these cars either automatic or power driven. We were probably lucky we had some kind of windshield wipers. In fact, the intermittent wiper system didn’t even go on to automobiles until the 1969 Mercury installed the first.

I restarted the car and pulled up the hill without a hitch, a pause, a jerk or a gear grind.

“I want you to do a three-point turn and take us back.”

This was the last step in the test. All I had to do was execute a three-point turn and I was done. I turned forward into the first point. I backed up and my rear bumper just scraped the embankment behind the shoulder.

“Is that it?” I asked weakly.

“That’s it,” he said, noting on the clipboard that I had failed.

I had failed my driver’s test. I was mortified. I would have to come back another time and go through all this tension again.

No comments:

Post a Comment